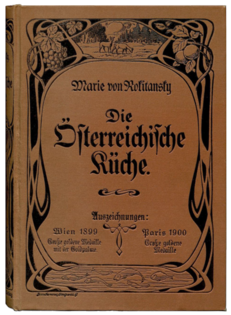

In 1897, Marie von Rokitansky published “Die Österreichische Küche” (the Austrian Cuisine), a collection of several hundred recipes all of which she had herself tried out in her kitchen in Innsbruck. There were raving reviews, as the pundit felt the volume contained the best dishes that the land of the Habsburg monarchs had to offer: alongside the schnitzel and strudel recipes you would expect to find, there were also unusual soup recipes from Qatar and Indian curry. Including these dishes in a book on Austrian cuisine attests to an image of Austria that was not trammelled by narrow nationalist definitions or the Imperial borders of the Empire; rather it was interwoven with a global network of ideas and tastes.

Historian Amy Millet takes precisely this fact as the starting point of her Ph.D. project. In it, she shows the international history of Austria’s modernization in the long 19th century quite literally at the kitchen table and explores the question of how cuisine fostered and represented a national identity. To date, studies of Austrian identity have tended to foreground the nationalistic ideologies of the day or the cultural and political institutions on which the Habsburg monarchy relied in order to secure the loyalty of its citizens. Put differently: they have focused on the interaction between individual and state. By contrast, Amy Millet starts her analysis not with associations, ideologies, or schools, but with people’s everyday lives in Vienna and Graz, and goes on to ask what contribution in Habsburg Austria did culinary practises such as cooking, shopping and going out for meals make to developing notions of an Austrian identity in the 19th century. To what extent does consumer behaviour strengthen or undermine nationalist feelings? Did consumer patterns express other identification characteristics that were more influential than belonging to a nation, such as class consciousness, imperial and/or cosmopolitan ambitions or gender solidarity?