Körperflüssigkeiten und -ausscheidungen der Götter des Alten Ägypten

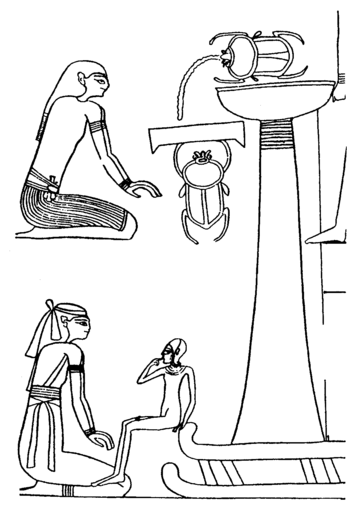

Spitting scarab beetle which can symbolize the God Khepri, Thebes, Grave of Ramses VI, Book of the Night, 12th hour of the night (redrawing)

Spitting scarab beetle which can symbolize the God Khepri, Thebes, Grave of Ramses VI, Book of the Night, 12th hour of the night (redrawing) (translated project title)

“And he cried in primordial water as he could not see his mother the cow, and humans arose from the tears from his eyes. He laughed on seeing them and the gods arose as saliva.” This is how a cosmogonic inscription in the Greco-Roman Esna Temple describes Ancient Egypt’s myth of the creation of humans and gods by the infant sun god. Life on earth arises from the omnipotent one’s secretions.

The bodily fluids and excretions of divine beings play a central role in many religions – one needs think only of wine as the blood of Christ. However, to date there has been no overview of this thematic complex as regards Ancient Egypt. Egyptologist Dr Natalie Schmidt has set out to fill this gap; she has been studying a period of some 2,500 years on the basis mainly of hieroglyphic and hieratic sources, starting with the texts from the pyramids and ending with the temples and papyri from Greco-Roman times. The secretions of the gods of Ancient Egypt make them at times seem decidedly human. Thus, gods hurt themselves or get wounded and shed red blood. They fall ill, catch a fever, or break into sweat. The child of the sun can first open its eyes after overcoming “bjdj”, a disease that causes the eye to ooze, and the God Osiris sustains a festering wound in the course of his coronation.

“Blood of Isis”, tjt amulet made of red jasper, 664–304 B.C.E., 2.5 cm

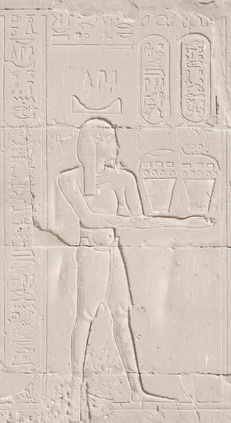

“Blood of Isis”, tjt amulet made of red jasper, 664–304 B.C.E., 2.5 cm Personification of the mining region of Jspd, where a green mineral equated with the divine eye secretion jnf, is found. Representation on a pylon in Edfu Temple on the west bank of the Nile, column base

Personification of the mining region of Jspd, where a green mineral equated with the divine eye secretion jnf, is found. Representation on a pylon in Edfu Temple on the west bank of the Nile, column baseHowever, the comparison with humans stops there as Osiris’s suppurating pus has creative potential: Together with the god’s blood he creates a holy site in the form of a lake. Similarly, the blood dripping from the God Seth’s nose brings life to the fields, and the earth god Geb spawns vegetation from his blood or his vomit. Like humans, the gods also mourn and cry tears, with the difference that these create new life or even bring the dead back to life. The emotional world of the gods of Ancient Egypt reflects that of humans, whereby their rage, for example, can have destructive traits – in particular if the Godhead in his fury assumes the form of a poisonous animal and thus also possesses the latter’s venom and is therefore equipped, for example, with the deadly breath of a spitting cobra or a scorpion’s poison. That said, the gods not only adopt secretions from the animal world but also characteristic behavioural patterns of the animals they embody and in this way attest not only to the strong bond to nature in Ancient Egyptian religion but also to the very detailed manner in which Ancient Egyptians observed nature. Depending on the god in which it originated, the seed of an inimical creature could spell potential danger for a god or goddess but could at the same time create new gods. Even if these and other bodily fluids imbue the Ancient Egyptian gods with a touch of humanness, the divinities nevertheless always remain superior to mere mortals and with their excretions gift all of Egypt life.

Dr Schmidt has identified and analysed a total of 15 secretions. In doing so she has compiled the first overall reference work on the bodily fluids and excretions of the Ancient Egyptian gods along with the relevant terminology. In it, she characterizes each secretion by function and elaborates on the sacred interpretations, assessments, and the divine, local, cultic and architectural relationships involved. She submitted her findings as a doctoral thesis to the Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen and it has since appeared in two volumes issued by Harrassowitz Publishers and entitled “Körperflüssigkeiten und -ausscheidungen der Götter des Alten Ägypten”.

Grant holder

Dr. Natalie Schmidt, Tübingen

Support

The Gerda Henkel Foundation supported the project by granting a doctoral scholarship and covering printing costs.

This project was documented in spring 2023.